Back-to-Back Theatre

Geelong Performing Arts Centre, March 3, 2013

Ganesh Versus the Third Reich is a play about power. It is, as one cast member puts it, a very powerful play. Most critics and audiences concur. There’s no doubt that Back to Back theatre have produced an engaging and highly unsettling work, yet it raises questions about the ethics of its own creative process and the audience’s consumption of the work that cannot be easily resolved. This ethical ambiguity makes it one of the most intellectually ambitious, and emotionally harrowing pieces of theatre I have ever seen.

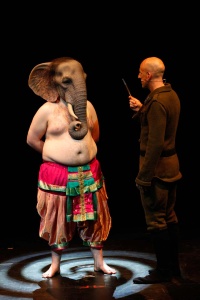

Back-to-Back theatre is a unique company. Some of its members have intellectual disabilities, and these disabled people work alongside ‘normal’ artists under the artistic direction of Bruce Gladwin. Together they have produced a multi-layered work about power, representation and appropriation. In short, the play is about the politics of making a play with intellectually disabled people who may or may not be fully aware of what they are doing. This is a piece of meta-theatre that skillfully weaves its two narrative threads together in a mutually enriching manner. One story concerns the Hindu deity Ganesh, the elephant god, who is on a mission to reclaim his sacred symbol, the swastika, from the Nazis. This is a story suffused with myth, an apparently simple tale of good versus evil, right against wrong. Ganesh is a hero who must overcome a variety of obstacles before realising his goal, and defeating the evil Nazis.

The other story is about the process of devising this first tale, and presents the power dynamics involved in the creative process. David Woods plays a director who is attempting to shape and rehearse the Ganesh story. The choice of pitting Ganesh against the Nazis is an inspired one. The Nazis, as we all know, we are obsessed with racial purity, and attempted to exterminate those members of its own population deemed degenerate or abnormal. The notorious Dr. Joseph Mengele, the so-called ‘Angel of Death’, conducted experiments on so-called ‘mongoloids’ in the interests of ‘science’. The Nazis are the perfect villains, and Ganesh’s quest to re appropriate the Nazi symbol is righteous. The Nazis remain exemplars of fascism, and authoritarianism. David Woods’ character is a mostly benevolent dictator who is prone to fits of inchoate rage when things don’t go his way during the rehearsal process. He has what we might call an ‘artistic’ temperament’ and becomes frustrated with his collaborators throughout the play. His dictatorial behaviour turns him into a little Hitler (another person with an artistic temperament — let’s not forget that Hitler was a failed artist).

The Ganesh story is told with the aid a series of ingeniously simple techniques — masks, projections, and conventional stage lighting, which are visually stunning, but it’s the rehearsal that makes the most impact on the audience. The director treats his charges with tenderness and compassion at times, but he is also capable of losing his religion, and humiliating his cast when he loses patience with their limitations as actors. The play overtly draws attention to the fact that we, the audience, are watching actors who may have difficulty comprehending the distinction between fact and fiction, play and world. How is it possible to negotiate the ethics of working with people who may not be able to fully consent to the rehearsal process? And why do audiences attend Back-to-Back shows? What are they looking at exactly? These are some of the questions that the play raises. At one point Woods suggests that audiences want to see a ‘freak’ show, and the final image of the play which has one of the disabled actors framed by lights around the underside of a desk echoes this observation.

At another point, the director claims that the story in theatre, and other forms of dramatic entertainment like reality TV, is beside the point. Audiences, he claims, want to see real emotion, fraught situations, power dynamics. So, the quality of the food in Master Chef doesn’t really matter. The audience wants to see tears, they, we, want to see the ugly power dynamics involved when people are divided into masters and slaves. Reality TV is about manufacturing heightened emotions by turning, for example, weight loss, into a grotesque spectacle or ritual humiliation. It matters less how many kilos evaporate in the gymnasium than how many tears are shed in the dissolution of a hapless contestant’s self respect and dignity. The director in the play, superbly played by David Woods, throws this insight about the politics of spectatorship at his audience. Why are we in the theatre? Are we watching a ‘freak show’?

Of course, exposing the ethical problems associated with making Ganesh Versus the Third Reich does not absolve the company itself from its complicity with the power mechanisms that are involved in the play. To what extent does the theatre company treat their actors like ‘freaks’? To what do they exploit them? Such complex ethical questions cannot be resolved. The play, in many ways confounds stereotypes about people with intellectual disabilities while simultaneously creating the uneasy suspicion that the play is some kind of freak show.

Perhaps it might be more productive to think of Ganesh Versus the Third Reich as a Foucauldian power play. Michel Foucault consistently railed against the normative tendencies in the administration of social and political life, against the way institutions categorise and sort people into specific classes in order to maximise their productivity. He also claimed that power is never simply possessed by any specific person or institution. Rather, it makes more sense to speak of power relations that are always at play in every human transaction. Power may oppress, but it may also provide a starting point for resistance, it might also function as a positive force that unsettles the desire for normativity. Ganesh Versus the Third Reich is a play about Power Relations. Make no mistake, this is a stone cold classic, and theatre rarely gets to be this good.